How to integrate nature-based solutions into their climate and nature-positive strategies.

What does compensation mean, and what role does it play in corporate impact reduction pathways? What are the most suitable approaches and tools?

A short guide to help companies understand how to credibly, effectively, and responsibly integrate nature-based solutions into their climate and nature-positive strategies.

Introduction: The Importance of Being Honest

It’s a dynamic time to work in sustainability. A growing number of companies all over the world are making commitments to reduce emissions and play their part in decarbonising the global economy. According to the latest data, enterprises covering 34 % of the global economy by market capitalisation have committed to net-zero emissions using Science-Based Targets, while more than 140 countries – accounting for about 90 % of global annual emissions – had announced or are considering net-zero targets in line with the Paris Agreement.

At the same time, we are coming to understand that not all climate commitments or action plans are equal, and the risk of greenwashing has kept pace with climate action. Increased scrutiny from regulators, civil society organizations, and news media has raised awareness about the proliferation of false, misleading, miscalculated, or oversimplified climate-related claims based on poor-quality compensation projects and/or low integrity corporate climate strategies ( → See Section 3).

In particular, attention has focused on misleading claims resulting from nature-based solutions (NBS) like tree planting or forest protection, with many companies – notably Nestle, Gucci, and Kering – recently pulling back on their nature-related investments due to uncertainties concerning their validity or relevance.

Concurrently, several political, financial and commercial drivers are pushing the transition towards responsible corporate climate performance while exposing non-compliant companies to legal and reputational risks. Mandatory extra-financial disclosure frameworks like the CSRD and restrictions on green claims from the EU Green Claims Directive are forcing tighter and more narrow pathways for implementing climate strategies. In parallel, investor and consumer demand increasingly directs funding towards business activities demonstrating a credible and reliable commitment to sustainability.

Many companies feel squeezed on both sides – on the one hand, it’s clear that the private sector plays a critical role in closing the financial gap for biodiversity and climate change mitigation by supporting ecosystem conservation and restoration; on the other, companies are unsure how they can responsibly and credibly integrate nature-based solutions into their sustainability transition plans.

So, what is the role of NBS in a credible climate strategy? How do we reconcile uncertainty with urgency? How can we distinguish between evidence-based action and greenwashing? How can we embed honesty in our ambitions? To answer these questions, we must first take a step back and agree on a few fundamental terms.

Key terminology

There is currently a lot of confusion about the proliferation of specific and technical terms associated with corporate climate strategies. Language is important as responsible and credible pledges must be based on transparent communication to inform all stakeholders fully and unambiguously. To understand the relationships between financial instruments to remunerate nature-based solutions, their use in carbon inventories and the resulting impact on companies’ climate credentials, we first need to distinguish between nature-based impact statements and the way these statements are used by sponsors – in other words, we need to distinguish nouns from verbs.

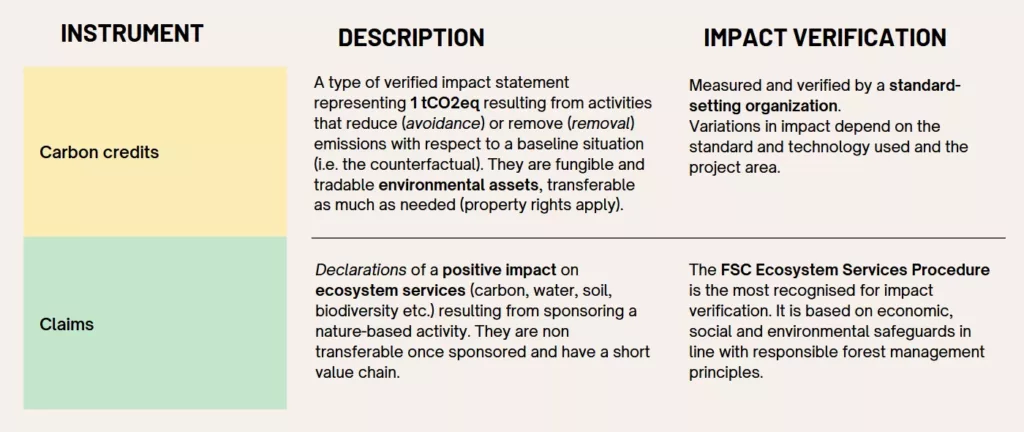

Nature-based impact statements, such as carbon credits or pure claims, are nouns. They represent a real, tangible impact on the ground. The table below shows the main features:

Figure 1. Main features of two types of nature-based impact statements

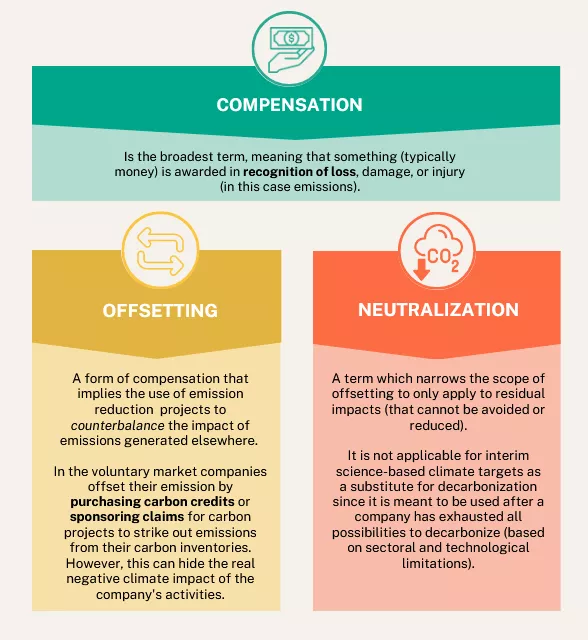

On the other hand, practices like offsetting, neutralization or beyond value chain mitigation – which are all different forms of compensation– refer to the use of verified impacts, i.e. they are verbs, as explained in the following infographic:

Figure 2. Different uses of verified impact statements

Nature-based impact statements (nouns) and their strategic use by companies (verbs) are combined in different ways and to varying extents to substantiate claims about overall company emissions performance – e.g. Net Zero, Climate/Carbon Positive, etc.

This distinction was made to emphasize a fundamental concept. The terms ‘carbon credits’ and ‘offsets’ are not interchangeable. Carbon credits can be used to back up corporate claims of offsetting emissions or can be a tool for channelling climate investments (compensation) without any offsetting claim.

In fact, new approaches to climate commitments are recently emerging, which assume “compensation” without the use of “offsetting”, i.e. emissions not being erased from carbon inventories. One effective example is the climate contributions model, which allows companies to take responsibility for their emissions by directing a proportionate share of financial resources for climate action beyond their value chain without claiming to offset or neutralize any actual emissions. In this way, compensation measures will be complementary – and not alternatives – to impact reduction actions, overcoming all the drawbacks of offsetting and providing a clear indication of the company’s level of climate ambition.

Lose-Lose: The Pitfalls of Compensation

Given the different nuances of the term compensation, let us now analyze both the reasons why it is shrouded in mistrust and those that should justify its use. There are mainly two types of risks related to the use of project-based emissions avoidance/removals for compensation:

- The compensation project is of poor quality: the positive impact (carbon) is not there.

Nature-based compensation projects usually rely on the AFOLU (Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use) sector to protect existing carbon storage (e.g. reduce carbon released from forests) or enhance atmospheric removal (i.e. increase absorption).

However, there must be robust rules ( → see Next section) offering a solid guarantee that the amount of carbon certified has been permanently (or at least for an adequate time) and truly avoided or removed. When these are not respected, not only the existence of a concrete positive impact of the project is undermined, but also the reliability of the whole compensatory logic. As an example, the recent scandal involving VCS-Verra has shown the considerable effects in terms of visibility and credibility that result from not meeting quality criteria.

- The climate strategy does not meet integrity requirements: a company misuses the carbon claim.

Poorly planned climate strategies with an overdependence on offsetting can discourage (or often replace altogether) emissions reduction within a company value chain, eventually delaying global climate action. This is a result of multiple drivers, namely the complexity and cost of rapid decarbonization combined with the low price of carbon credits in recent years, which made the cheaper alternative preferable. However, this perverse substitution effect – that hides an implicit license to pollute – does not reflect the true value of the impact caused. Moreover, many organizations do not clearly and transparently distinguish between reduced and offset emissions in their climate-related disclosures, obscuring their reliance on offsetting to meet their targets.

Unfortunately, we sometimes see both risks happening at the same time: some companies are relying heavily on offsetting derived from poor-quality carbon credits to drive their climate strategy.

This is what we call a “lose-lose” outcome because capital is allocated away from decarbonization plans towards impacts that do not produce tangible benefits for climate change mitigation.

Win-Win: Responsible Compensation

However, if conducted appropriately, compensation can also have beneficial effects in contributing to meeting global emissions reduction targets.

Indeed, it is a way for companies to:

- Internalize the social cost of GHG emissions. Recent studies (Ecosystem Marketplace, Trove Research) have shown that companies that take responsibility for a significant percentage of this cost on an annual basis (i.e. by purchasing carbon credits) are decarbonising twice as fast, pay three times as much for emission reductions within the value chain, and are three times more likely to have an approved science-based climate target than those that do not.

- Act now to invest immediately toward combating the global climate crisis. Many decarbonization strategies – reducing inefficient processes, switching to renewables, engaging with supply chains – require massive overhauls of our current economic and infrastructural systems that will take years to decades to implement. Effective nature-based compensation strategies allow companies to show progress toward their commitments in the short- to medium-term, often with many other core benefits on biodiversity, water resources and other ecosystem services.

- Neutralize unbeatable emissions. Some companies – and some entire sectors (cement, iron, steel, chemicals) – will likely not be decarbonized by 2050 due to economic and/or technological limitations. Compensation is needed to neutralize these residual emissions in the long term.

- Go beyond decarbonization to net-negative emissions. Any IPCC scenario that limits us to 1.5 °C warming includes 5-10 GtCO2e/yr of removals beyond net zero. This requires us to remove many of the emissions we have already emitted.

How to set a responsible climate framework: best practices to reduce your impact

In order to avoid the risks mentioned above and effectively reduce its climate impact, a company has to design a robust climate strategy to be applied throughout its entire value chain and rely on quality projects that guarantee real emission reductions.

The Mitigation Hierarchy

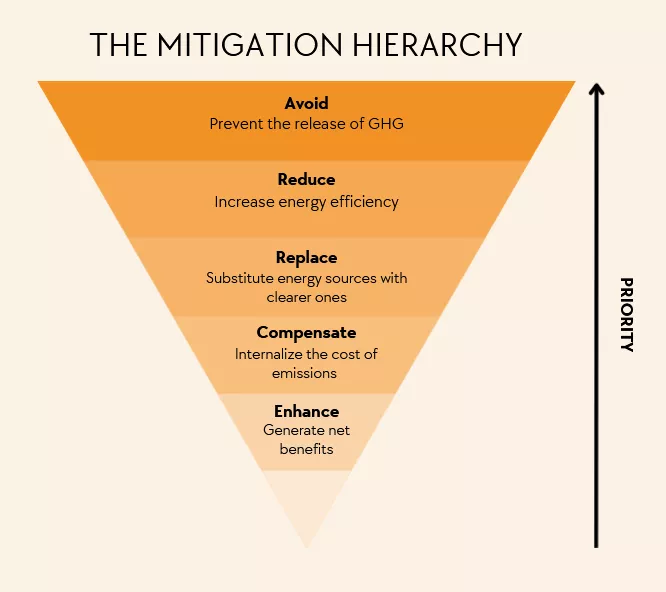

A responsible approach to managing impacts involves following the GHG mitigation hierarchy, i.e. a multi-stage priority order that requires implementing all possible measures for each step before moving on to the next (see figure below).

This implies that first, it is necessary to avoid or prevent emissions from the outset; then to reduce the intensity of impacts that cannot be avoided; then to replace the most polluting emission sources; and only as a last resort compensate for emissions that cannot be reduced because of technological limits (the so-called hard-to-abate or residual emissions).

Figure 3. The Green House Gases Emissions Mitigation Hierarchy

Currently, the reference procedure for corporate climate action is set by the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), which allows companies to define an emission reduction pathway assessed in line with scientific data and best practices for the sector of interest.

However, these good practices are complex to contextualize and operationalise for enterprises, which often rely on the support of expert consultants. This is why Etifor developed the MARC approach – Measure, Avoid, Risk, Capture and Communicate – which simplifies and makes the process proposed by the SBTi easier to interpret and implement.

MARC enables a company to measure and assess its climate impact across the 3 scopes; to take full responsibility for it by implementing a science-based emissions reduction strategy in line with global targets, while mitigating risks that may affect the value chain; and to ensure transparency in communication of impacts to stakeholders.

| Box 2. Learn more about the MARC approach: https://www.etifor.com/en/marc-approach/ |

Quality criteria for nature-based projects

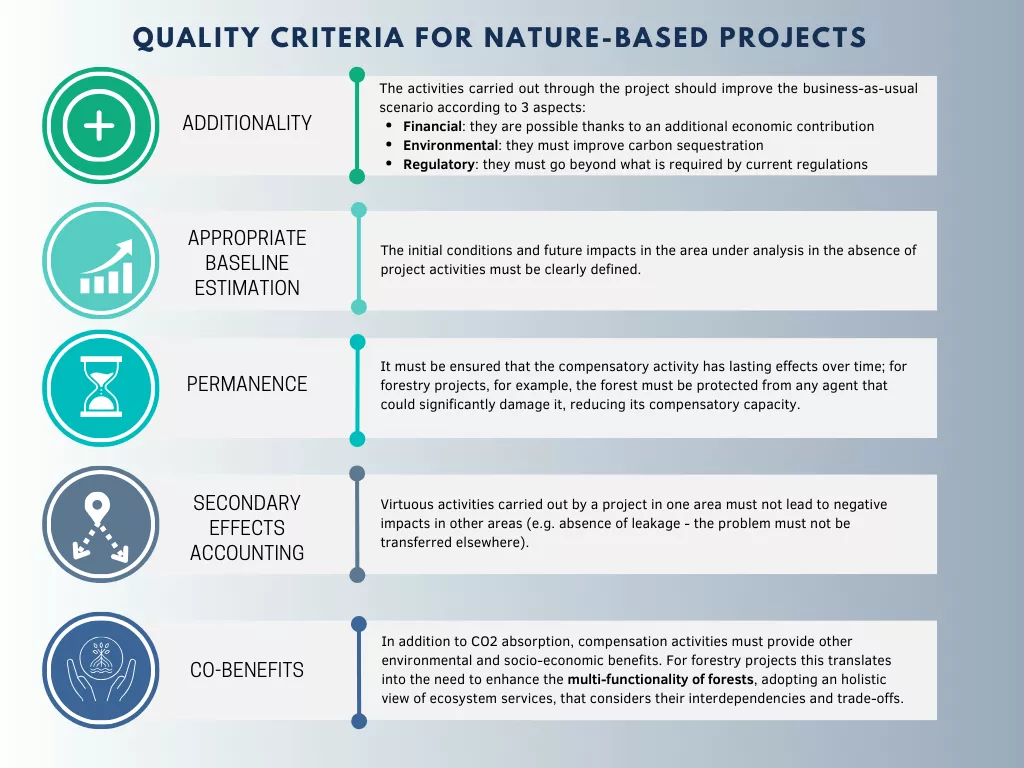

Drawing on best practices derived from the scientific literature, national and international guidelines and the main accreditation standards, we can distinguish two main categories of quality criteria for nature-based compensation projects: core principles and policy aspects. The core principles ensure that all relevant emissions factors for the accounting are included, and that the calculation methodology is consistent, transparent, accurate, and conservative. The policy aspects include other quality criteria that don’t concern the actual calculation of GHG emissions/avoidance but are nonetheless very important to ensure the concreteness, effectiveness and durability of the positive impact over time. These are illustrated in the table below.

Figure 4. Quality criteria for nature-based projects.

Alongside these quality criteria, a compensation activity must then be certified by an independent, third-party body that validates its compliance with the methodology adopted and the impacts generated.

Connecting the dots: when integrity meets quality

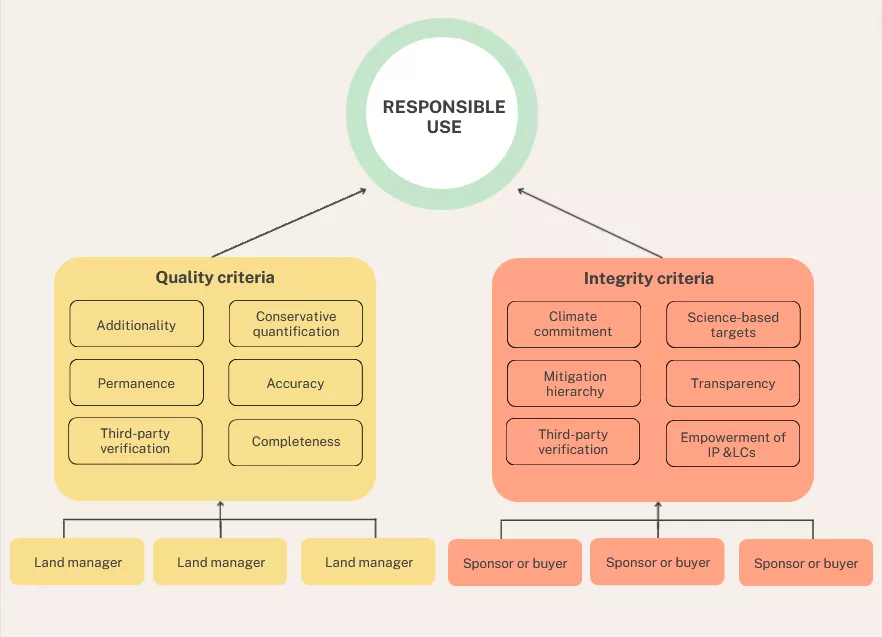

To summarize what was said in the previous sections, the following picture shows how quality criteria for impacts and integrity criteria for buyers or sponsors meet to make responsible use of nature-based projects for compensation.

Figure 5. Key elements – demand and supply side – for the responsible use of Nature-based solutions.

Conclusions

As we have seen, nature-based activities have great potential to accompany businesses in their transition to sustainability and reduce emissions on a global scale. However, the recent criticism against unqualified climate-related claims has highlighted the need to address corporate climate action with a system-thinking approach that considers the issue in its complexity.

For this reason, in the coming years, we expect more and more companies to adopt increasingly robust, ambitious and well-designed strategies, from Net Zero to Climate Positive, or go further to contribute to a Nature Positive outcome – considering co-benefits on several other closely interlinked environmental domains. Within this paradigm shift – that inscribes climate in a broader ecological framework – it will be necessary to invest in high-quality, integrated solutions for the well-being of nature as a whole, thereby shaping a positive structural change towards which the global economy will have to strive.

Learn more about the Nature Positive approach